by: Mosleh Ahmed FCA,

Director, The Professional Consortium and CEO, Microinsurance Research Centre.

What is Microinsurance?

Moving towards poverty reduction requires not just the generation of income among the poor. These incomes also require protection through effective risk-management. Insurance is an ex-ante risk management tool through which individuals and businesses are provided with financial protection. There are many market-based insurance products and processes designed to address the life cycle risks faced by people on a daily basis. For the people at the bottom of the pyramid, microinsurance is such an insurance product.

Insurance for low-income communities is not a new concept. Industrial insurance that was popular in Europe and USA in the 19th and early 20th centuries is the predecessor of today’s microinsurance. Though the word “microinsurance” appeared in the microfinance scenario in the 1990s, the concept of microinsurance has been around for over 40 years. La Equidad, a cooperative in Colombia started offering microinsurance to its members in 1970. Gono Shayestho Kendra, a healthcare provider in Bangladesh, launched a health microinsurance programme for the rural poor in 1972. Delta Life Insurance Company Limited, a regulated insurance company in Bangladesh, developed its Grameen Bima product – life insurance with saving for the rural poor – in 1988.

Very simply, microinsurance refers to the provision of insurance to low-income households; however, even today there is no standard definition of the concept despite its 40 years of existence.

The Consultative Group for Assisting the Poor (CGAP) Working Group on Microinsurance, now known as the Microinsurance Network, defines microinsurance as the protection of low-income people against specific perils in exchange for regular monetary payments proportionate to the likelihood and cost of the risk involved.

The International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) defines microinsurance as an insurance that is accessed by the low-income population, provided by a variety of different entities, run in accordance with generally accepted insurance practices, and includes insurance core principles.

The Microinsurance Centre states “microinsurance is the provision of insurance services to low-income people”.

In Lloyd’s 360 Degrees Risk Insight Report microinsurance is defined as insurance that is designed specifically for the low-income market.

Microinsurance Centre states “microinsurance is the provision of insurance services to low-income people”.

In a joint research report by UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and Germany’s The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH microinsurance has been defined as insurance that is accessible to the low-income population, provided by a variety of different providers and managed in accordance with generally accepted insurance practices.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has described microinsurance as a risk management system involving low-income groups in which individuals, businesses, or other organisations pay a certain sum of money in exchange for guaranteed compensation for losses resulting from certain perils under specified conditions.

In a report by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) microinsurance has been defined as a subset of insurance that provides financial protection to the poor for certain risks in a way that reflects their cash constraints and coverage requirements.

Different stakeholders look at microinsurance from the point of view of their own use and define it from that angle, hence the variety of definitions. Governments look at it as social protection. Donors focus on its potential to secure poverty reduction. Commercial insurers see its potential as a way of reaching large under-served markets. Analysts refer to it to highlight the size of the market at the “bottom of the pyramid”. Academics look at it as an essential financial service for sustainable economic growth. Microfinance practitioners look at it as the “next step forward” in financial inclusion. But the poor consider it an “unnecessary” expenditure that they find hard to finance from their scarce cash resources.

All of the above definitions of microinsurance are almost the same as that for conventional insurance except for the clearly prescribed target market: low-income people. These three words change the whole character of microinsurance. The definitions also indicate that microinsurance should be funded by premiums and managed on generally accepted risk-management principles. Microinsurance, therefore, excludes social welfare as well as emergency assistance provided by governments. It is a tool that can be used to increase the social protection of the low-income population.

Microinsurance is not charity – it is a business. However, it requires insurers to change their mindset. It challenges the insurers to go back to the drawing board and find quick, cheap and simple solutions to provide cover for people who have very little ability to pay. Microinsurance business operations can be sustainable and if appropriately designed and delivered, it can play an important role in reducing the vulnerability of the poor and open profitable markets for commercial insurers. Microinsurance also proves that low-income people are insurable just like microcredit proved that the poor are creditworthy.

Purpose of Microinsurance

Poverty and vulnerability reinforce each other in a downward spiral. Not only does exposure to risks result in substantial financial losses for the poor, vulnerable households also suffer from the ongoing uncertainty about whether and when a loss might occur. Because of this perpetual apprehension, the poor are less likely to take advantage of income-generating opportunities that may arise and reduce their poverty.

The vulnerability results from the inability of the poor to deal with the losses or costs resulting from the occurrence of a risk event. The poor are more vulnerable to many of the life-cycle risks than the rest of the population, and they are least able to cope when a crisis does occur. The role of microinsurance is to reduce the vulnerability of low-income households.

The objective of microinsurance is to reach the low-income people by offering insurance with lower premiums and more rapid payouts than are available under traditional policies. It is normally offered to people who do not have access to conventional insurance policies, and who usually live in more vulnerable conditions. This vulnerability of the poor and the inefficiency of the traditional risk-management techniques they employed are the two main factors that motivated the development of microinsurance in many countries.

The purpose of microinsurance is to extend financial inclusion in the insurance domain. The objective of financial inclusion is to allow individual consumers, particularly low-income consumers currently excluded from formal financial sector services, to access, and on a sustainable basis, use the financial services that are appropriate to their needs and provided by regulated service providers.

The target population of microinsurance is the poor and the vulnerable poor, not the ultra poor or the destitute. The target population can be defined by exclusion: the families or people whose income is so low that they are excluded from standard insurance markets. However, many people in the target population of microinsurance are not in such extreme poverty that they fit into social security and income-transfer programmes (Churchill, 2006). Furthermore many people in the target population are poor and destitute and do not have the resources to pay the premium. The state is responsible for the ultra poor and the destitute; they are outside the scope of microinsurance.

Why do the poor need Microinsurance?

Uninsured risk leaves poor households vulnerable to serious or even catastrophic losses with negative shocks. It also forces them to undertake costly strategies to manage their incomes and assets in the face of risk, and lower their ability to earn income. Welfare costs due to shocks and foregone opportunities to earn have been found to be substantial, and have contributed to persistent poverty in many developing countries (Murdoch, 1990).

Microinsurance has the potential to reduce these financial shocks, uncertainties and welfare costs. By offering a payout when an insured loss occurs, it avoids other costly ways of coping with the shock, leaving future income earning opportunities intact.

There are three categories of risk-managing financial products available to the low-income households: depleting liquid savings that they can use to reduce the effects of an economic stress; emergency loans to tie them through the crisis period; and microinsurance, that pays compensation after the event has taken place. Of the three, insurance in the only option that can be pre-planned in accordance with household income.

While microcredit helps people to grow economically and to move out of poverty, microinsurance helps make this growth sustainable and prevents poor people from falling back into poverty. It is a safety net that pushes them back above the poverty line with financial compensation whenever they suffer a financial loss due to a risk event and slip below the poverty line. Because of this fundamental link with credit, micro insurance is often sold by microcredit organisations, and often offered in combination with loans. Some microfinance institutions sell insurance as an additional service. Others make insurance compulsory for their clients, for reasons ranging from reduced credit risk to building an insurance culture.

The low-income households are exposed to a variety of risks throughout their lives. Table 1 below shows the life cycle needs and perils faced by the poor:

Table 1: Lifecycle Risks and Needs of the Poor

Based on a presentation made by Microinsurance Centre

Of all the life cycle risks shown above, the following perils affect the low-income households most adversely:

- Illness or injury (health)

- Death (bread winner or close family member)

- Loss of valuable assets through fire, natural disaster or theft (asset protection)

The financial cost to a household that loses a valuable asset or a breadwinner is reasonably clear and can be substantial. The impact of on-going uncertainty about whether and when a loss might occur is not easily understood but is nonetheless more damaging. The uncertainties make the low-income households hesitant and prevent them from availing many economically beneficial opportunities. The security linked to being insured allows low-income people to take timely decisions and avoid costly risk-management strategies with positive impacts on poverty reduction.

Microinsurance stakeholders

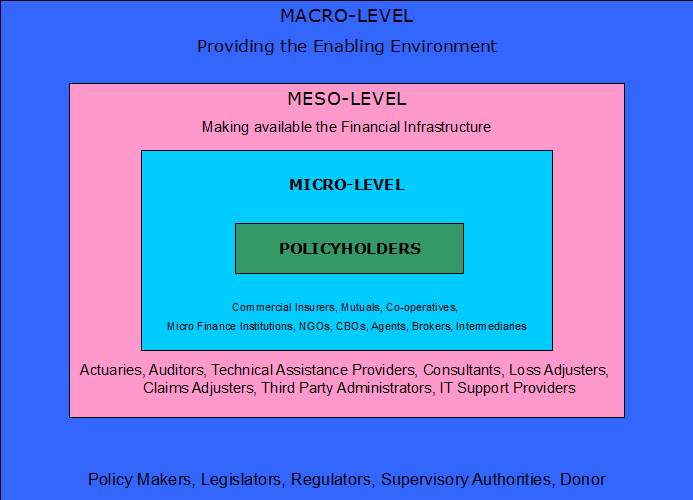

A range of players and institutions are involved in the microinsurance value chain. Each of them is a stakeholder. They include insurance regulators, risk carriers, administrators, policyholders, delivery channels, technology platforms, and related service providers. The microinsurance value chain has three distinctive levels at which the stakeholders interact with each other. Table 2 below depicts them.

Table 2: Microinsurance Value Chain

Based on a presentation made by Microinsurance Centre

The Micro-level

At the micro-level, the policyholders are at the centre and everything revolves around them. The policyholders could be individuals or a cohesive group or members of an organised group. When provided on a “group basis”, the underwriting process is simplified and the cost of microinsurance is reduced substantially

The next important player at the micro level is the insurance provider. While MFIs (Microfinance Institutions)/NGOs (Non-governmental Organisations) enter this market for the benefit of their members, commercial insurers are in microinsurance for multiple reasons. Through a multiple choice questionnaire Coydon and Molitor found in 2011 that 39% of the commercial insurers are in the microinsurance business in order to enter a new market, 27% entered in expectation of financial profit, 23% entered due to corporate social responsibility, 21% are in it for image/brand recognition and 16% entered to expand to new countries.

The provider can be a single institution that carries the risk, markets or distributes the products, and administers the policy. Sometimes these tasks are carried out by separate organisations. The insurer might carry the risk and another organisation, such as a MFI, NGO, CBOs or Cooperative, may distribute the product and collect the premium. A specialised administration provider called a Third Party Administrator (TPA) might undertake the administration of the service. Administrators offer specialised back-office support and/or claims processing in the supply chain. The risk carrier or delivery channel also may accomplish these functions.

The segregation of responsibilities often leads to a reduction in costs and thereby an overall reduction in the premium. This makes microinsurance more affordable to low-income households.

The microinsurance industry is constantly innovating new linkages between various players at the micro level. Many initiatives have been launched by major supporters of microinsurance to encourage the development of new microinsurance concepts and encourage support from other stakeholders, practitioners and policy-makers to contribute to new innovations and to further the extension of microinsurance to all low-income households.

The Meso-level

Meso-level activities in a microinsurance value chain facilitate the micro-level activities of microinsurance. They provide the critical support required for the smooth functioning of microinsurance schemes. They include actuaries, claims adjusters, IT providers, software providers, Information System providers, trainers and other facilitators. They are often the linkage between micro-level and macro-level players and effectively drive the other two levels. Technology platforms enable the processing of services across the chain and include electronic media, such as personal digital assistants and mobile phones or social mechanisms, such as group-based premium collection.

The Macro-level

At the macro-level the stakeholders are governments and donors. The government needs to establish the right legal environment under which microinsurers can operate. Insurance regulators have a vital role in the sector to protect consumer interests and institute a legal and policy framework for microinsurance. Donors lobby the government to create the right environment and facilitate governments’ activities with financial and technical support. Both stakeholders’ main aims are to protect the microinsurance policyholders and develop the industry. Governments also need to establish supervisory mechanisms so that they can ensure that the various players operating microinsurance schemes in the country are in compliance with the law.

The government may also play a role in establishing consumer protection by setting up an ombudsman or a mechanism for registering grievances from dissatisfied microinsurance policyholders and assisting them in obtaining an equitable solution.

Demand for Microinsurance

The demand for microinsurance grows out of the risks and risk-management strategies of low-income households. Client demand is an essential prerequisite for any microinsurance programme. Demand is often assumed to be present, misunderstood or over-simplified by most microinsurance providers. In many microinsurance programmes, this misunderstanding has resulted in products and services that failed to meet the needs of the low-income households. Many insurance providers assess the demand based on what is available in the market, rather than establish through research what the low-income households require. Demand research reveals the need among low-income clients of finding more effective ways to cope with risks, even though clients rarely see insurance per se as a way to bridge this gap.

Insurers often use existing market studies and surveys as a base to quantify client demand and design suitable microinsurance products. Such products, however, must be customised to suit the varying requirements of the local population. The products must have the features of simplicity, availability, affordability, accessibility and flexibility; they must be need-based and demand-based. Serving the low-income market requires insurers to understand the localised needs of their clients and to develop and promote customised products to meet their needs. However, since client need is location-specific and is based on a given point in time, generalising demand across countries and regions will result in inappropriate microinsurance products.

Analysis of demand for microinsurance is extremely important for formulating policies and strategies for the low-income sector. An adequate knowledge as to the extent, determinants, and elasticity of microinsurance demand is essential to ensure proper utilisation of the existing resources, and to improve the quality of services. Analysis of demand is also crucial for designing strategies aimed at achieving the financial sustainability of a programme.

The challenge for microinsurance is to turn risk-management from a reactive to a proactive process. This begins with an understanding of the demand for a particular microinsurance product.

Microinsurance products

A variety of microinsurance products are available for the poor today. The appropriateness of some insurance products is questionable. Many of the products have been developed based on the needs of the poor as perceived by insurers. NGOs/MFIs mainly offer credit life insurance to protect their own loan portfolios. Many commercial insurers entering the market tend to scale-down their existing products rather than develop new, responsive products for the sector. Microinsurance products offered by commercial insurers are usually limited to life insurance and accidental death and disability as these are the least risky for the insurance providers and therefore the most likely product o be profitable.

Such products can be relatively expensive, excluding access by low-income households and often wrongly sold to them through unethical practices. In most cases, poor households are not able to continue payment beyond a few years resulting in lapsed insurance policy with the loss of their hard-earned cash.

The microinsurance product that touches most poor people is credit-life insurance, which is required to be purchased with microcredit and other borrowings. It can be very profitable for the insurer since the borrowers are often not aware that they have purchased insurance with their loans. Anecdotally, those insured with simple credit-life cover suggest that the product is not for them, but rather for the lender. Such products may not be the ones in highest demand by the poor and often not needed, considering that very few loan defaults are due to death of the borrower.

Some of the microinsurance products that are available today and the countries in which they are offered are shown below.

- Credit-Life/Life/Endowment

- Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Laos, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Vietnam,

- East Africa, South Africa, West Africa

- Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Venezuela

- Health/Critical Illness

- India, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Laos, Pakistan, Philippines,

- East Africa, South Africa, West Africa

- Colombia, Mexico

- Georgia, Russia

- Crop/Weather

- India, Philippines

- Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi

- Haiti, Mexico, Nicaragua

- Property/Asset/Livestock

- Bangladesh, India, Mongolia, Nepal

- East Africa, South Africa

- Albania

- Funeral

- East Africa, South Africa, West Africa

- Colombia, Mexico

- Integrated Package

- India

- Rural Insurance Schemes

- India

- Group Personal Accident

- West Africa

- Unemployment

- East Africa

- Flood

- China, Indonesia

Life insurance pays out benefits to designated beneficiaries upon the death of the insured. There are three broad types of life insurance coverage: term, whole life, and endowment. Term life insurance policies provide a set amount of insurance coverage over a specified period of time, such as one, five, ten, or twenty years. This insurance is appropriate when the policyholder’s need for coverage is temporary. This is the most widely used life insurance policy in low-income communities in developing countries and the least complicated for the provider to offer.

Whole-life insurance is a cash-value policy that provides lifetime protection. Endowment life insurance pays the face value of insurance if the policyholder dies within a specified period. Microcredit lenders invented credit-life insurance to protect their own loan portfolios. It is a term life policy, tied to the term of the loan. It pays off the balance of the loan in case the borrower dies before the full repayment of the loan. It is, in fact, a loan protection policy for the benefit of the lender rather than the borrower. In most cases, the risk is taken in-house by the lender. Unfortunately, the majority of microinsurance policies in existence today are credit-life insurance.

Health insurance provides coverage for illness and accidents resulting in physical injuries. NGOs/MFIs have realised that expenditures related to health problems have been a significant cause of defaults and people’s inability to improve their economic conditions. While coverage varies, many providers cover limited hospitalisation benefits for certain illnesses, and for the costs of physician visits and medicine. Some also make available primary health care services. Health insurance is complex and is difficult to operate; the risk of moral hazard is high and safeguarding against such risk is expensive. Very few insurers or NGOs/MFIs offer this product.

Crop insurance typically provides policyholders with protection in the event that their crops are destroyed by natural calamities, such as floods or droughts. The experience with crop insurance in developing countries and even in the developed economies has had unsatisfactory results. It is difficult and expensive to prove whether the loss is due to insured perils or due to negligence by the insured. A derivative of crop insurance is index insurance. Very few insurers or NGOs/MFIs offer this product.

Property insurance provides coverage against loss or damage of assets, which includes huts, houses, shops, contents and livestock. Providing such insurance is difficult because of the need to verify the extent of damage and determine whether a loss has actually occurred. It is difficult for most insurers and NGOs/MFIs to guard against such moral hazard. A few, however, do provide such coverage. A derivative of property insurance is index insurance.

Index insurance has been developed as a solution to the problems of crop and property insurance, especially for drought and excessive rainfall in the agricultural sector and catastrophic risks such as floods, earthquakes, typhoons and severe cold weather. An index insurance policyholder is not compensated on the basis of the loss but on a pre-determined index such as rainfall level or earthquake magnitude or temperature level. Once an index is calibrated and correlates well with actual losses, underwriting and claims verification costs for the insurer are minimal and moral hazard and fraud is virtually eliminated. With donor support, several countries are experimenting with various index products but very few have reached sustainability.

Crop and weather insurance are more complex and therefore very few organisations are offering them; Life insurance products are relatively easier and are more popular.

Microinsurance distribution

Distribution or Delivery Channel denotes an individual or an organisation that takes or helps in taking an insurance product or an insurance service to the policyholder and provides all the after-sales services. Any organisation that already has financial transactions with the poor, and has their trust, is best suited to act as a microinsurance distribution channel. Distribution may involve several different organisations. It may include insurance companies, NGOs/MFIs/CBOs, cooperatives, outsourced administrators, third-party payment providers, and client aggregators such as brokers and retailers. Microinsurers prefer to use existing distribution channels rather than agents for the following reasons:

- To gain credibility in the market by exploiting the relationship that the distribution channels have with low-income households.

- It is difficult for a full-time agent to generate sufficient commission to sustain a livelihood, as microinsurance premium-based commissions are too small and therefore they are not interested in selling microinsurance.

- Most microinsurance channels do other things as their main business, such as providing loans, selling groceries or distributing agriculture inputs, with insurance commission providing a supplementary income.

- The microinsurance business model has a greater chance of success if risk carriers can quickly achieve scale, which they can do by working in partnership with a distribution channel such as an NGO/ MFI/ CBO/ Cooperative that already aggregates large numbers of low-income persons.

Distribution does not only involve sales; it is a much wider concept than simply getting the insurance product to the client. Distribution refers to all interactions that take place between the insurer and the policyholder. This includes handling of policy applications, policy delivery, premium collection, policy administration, as well as all marketing, sales and handling claims activities. Distribution is thus a much wider service than just the selling of insurance.

The cost of selling, underwriting and of administering an insurance claim does not decrease in proportion to the value of the policy. When using traditional channels and processes, insurance companies cannot write policies with values below a certain threshold without pricing them unrealistically. Moreover, microinsurance is a low-cost, high- volume business; therefore, achieving scale through an efficient distribution system is crucial.

Achieving scale through cost-effective distribution is one of the biggest challenges faced by insurers in low-premium environments where customers are typically unfamiliar with insurance products and are often sceptical about the providers. In an effort to effectively reach as large a client base as possible, the emphasis is increasingly falling on innovative new distribution models as alternatives to traditional microinsurance distribution approaches, which typically rely on distribution through microfinance institutions.

Distribution channels are essential for bringing products to clients for whom insurance may be fundamentally new. Microinsurance generally engages organisations such as NGOs/MFIs as distribution channels. Because of the scale, and also because NGOs/MFIs are already working with the low-income households and can deliver microinsurance at no additional cost, a premium-based commission becomes attractive to such organisations. In addition to NGOs/MFIs, organisations such as post offices, cooperatives, labour unions, employers and other institutions with large networks have the potential to reach significant numbers of clients at low cost.

A 2011 Coydon and Molitor report shows the following distribution partner pattern:

- MFI/Rural Bank 30%

- Agents 14%

- NGOs 11%

- Retailers, Service Providers, Funeral Parlours 11%

- Brokers 10%

- CBOs 10%

- Government and Semi-government 8%

- Employers 7%

- Faith-based Groups 6%

- Cooperatives 5%

- Others 9%

Retail channels such as grocery and clothing stores are an interesting new innovation because they can be either formal or informal. While the formal retail chains have the advantage of a well-known brand, client data and transaction systems, they are often less convenient than informal retailers. While informal outlets, such as “mom and pop” shops, may have the advantage of proximity and frequency of use, they have so far not been particularly successful with regard to sales volumes, perhaps because people do not expect to buy insurance where they get their milk and bread or top up their mobile phones. Insurers have also found it difficult to develop an effective value proposition for informal retailers, leaving them with limited motivation to sell insurance (Smith et al., 2010).

In recent years there has been a dramatic rise in the use of mobile phones amongst low-income people in most developing countries. Mobile phone, therefore, has emerged as an innovative channel for reaching the low-income people and carrying out financial transactions. In countries like Brazil, Ghana, India, Kenya and the Philippines there is an increasing trend of using mobile phone service providers as distribution channels. In a number of developing countries, Mobile Phone Network Operators (MNOs) have made it possible for customers to pay for their premium using their existing pre or post- paid mobile account. The advantage of this payment mechanism is that any customer with a mobile phone can use this option.

In addition to MNOs, a number of niche players like Bima, MicroEnsure and Trustco have emerged as specialists in bridging the gap between insurance companies and MNOs. Their products leverage airtime dealers and mobile money agents as channels for sales, premium collection and claims payment.

Because microinsurance premiums are small, distribution channels more often tend to be institutions rather than individual agents. An agent can earn much higher a commission from selling a conventional insurance product than a microinsurance product, whereas an NGO/MFI or even a retailer is already working with a large group of people and can convert their clients into microinsurance clients without much additional cost. A variety of businesses and organisations are engaged in microinsurance and they often join forces in diverse, and at times, innovative ways to deliver services to clients. Typical distribution/delivery models include:

- Partnerships between commercial insurers and MFIs and other delivery channels

- Regulated insurers that serve low-income clients directly, often with separate agents

- Healthcare providers offering a package, which includes both insurance and healthcare services

- Community-based organisations (CBOs) that pool risks and/or funds of members

- MFIs that offer insurance to their clients and act as risk carriers themselves

- Public Private Partnership (PPP) – government or donor partners with insurers/NGOs/MFIs to provide microinsurance to NGO beneficiaries.

A variety of institutions can and do serve the poor with insurance products. The challenge is to minimise the trade-offs in each model and ensure that different entities are able to offer services that are customised for the poor population. In one new innovation insurers are partnering with institutions traditionally not involved in insurance. These alternative distribution model partners have a community presence larger than what insurers could achieve on their own. Their infrastructure could be physical, such as store buildings, or virtual, such as mobile-phone networks.

Examples of recent innovation in distribution channels are:

- Cash-based retailers such as supermarkets and clothing retailers, offering simplified personal accident and funeral insurance products

- Credit-based retailers, such as furniture and electronic goods stores offering credit-life, extended warranties, personal accident and life insurance products;

- Utility and telecommunications companies offering disability, unemployment, personal accident and, in some cases, household structure insurance;

- Third-party bill payment providers offering personal accident and life insurance products.

Another breed of innovative distribution channel that has entered the market recently is the microinsurance intermediary. A microinsurance intermediary is an organisation that transfers the insurance risk from an NGO/MFI, cooperative or self-help group etc. to an insurance company. They work for a commission or a flat fee. An intermediary can also provide back-office services. Examples of intermediaries are MicroEnsure, First Microinsurance Agency Pakistan and PlaNet Guarantee. Examples of commercial intermediaries that have ventured into microinsurance are Aon, Marsh and Guy Carpenter.

Another new innovation in the distribution channel is where insurers do not collect premiums from customers at all, instead, they turn to a service provider or a product manufacturer to cover the cost of insurance or include the cost of the insurance in their service charge or product cost. Such a scheme generates customer loyalty, which benefits both the insurer and the service provider/product manufacturer.

Loyalty programmes are structured marketing efforts that reward, and therefore encourage, buying behaviour—behaviour that is valuable enough to the service provider or product manufacturer to justify subsidising the cover.

These types of models tend to renew the insurance policy every month, as long as the customer buys the service or product. When they don’t, the insurance benefit is forgone. A key success factor for such programmes is that customers become aware of the potential benefits of the insurance cover they are receiving.

Following are the characteristics of a good distribution channel:

- Regular transactions with low-income people

- Offer convenience and good customer service

- Enjoy the trust of their clients

- Have a large volume of customers that are potential policyholders.

- Be trustworthy to the insurer and the low-income people

- Have secure and efficient systems to collect and deliver premiums, and

- Provide transparent information on the cost of insurance services, coverage, and other performance

Source: McCord and Roth (2006)

Benefits of Microinsurance

Insurance services reduce the vulnerability of low-income households to risks against which they cannot afford to protect themselves. The risk-pooling mechanism of insurance makes protection more affordable. Besides this obvious development benefit, there is a subtle, indirect benefit of insurance: it creates financial incentives for insurance companies to encourage risk prevention. These financial incentives can lead to tangible development benefits that are produced by the private insurance market without prodding or funding from donors.

The list below shows some of the benefits of microinsurance for the various stakeholders:

Benefits for low-income households

- Products adapted to client needs

- Products adapted to client capacity to pay

- Products focused on loss of life and livelihood

- Reduced vulnerability to natural and other disasters

- Improves ability to cope with loss

Benefits for Intermediaries

- New line of business

- Larger policyholder base

- Improve morale among employees

- Corporate social responsibility

- Enhances corporate image

- Increases commission earnings

- Training and capacity building

Benefits for Insurers

- New line of business

- Larger policyholder base

- Improves morale among employees

- Corporate social responsibility

- Enhances corporate image

Social Benefits

- Improved morale among rural communities

- Increased ability to face problems

- Escape from cycle of poverty

Challenges of Microinsurance

Despite the success of many microinsurance schemes, there are many challenges in providing insurance protection to low-income households. These challenges are especially salient for the more complex forms of insurance, such as health, property and crop.

Restrictive regulatory environments: Insurance regulations in many developing countries are unintentionally biased against microinsurance providers. Regulations such as those involving minimum capital requirements, solvency, licensing, distribution and investment restrictions are often designed for the large insurance companies serving the middle and upper-income segments of the market. These regulations are restrictive for insurers trying to serve the low-income market.

The limited interest of commercial insurers: Commercial insurers in many developing countries are often unwilling to provide insurance for the low-income market, possibly because of traditional biases and beliefs regarding the attractiveness of low-income households as customers. As long as these traditional biases persist, they will continue to limit the participation of commercial insurers in low- income markets and will thereby slow the development of micro-insurance.

Minimising transaction costs: Low transactions costs are key for both the policyholder and the institution. If the costs are too high and there is an inconvenience in applying for insurance, paying a premium, and submitting claims, low-income households will be unwilling to purchase the insurance, regardless of its benefits. At the same time, microinsurance providers need to minimise their costs to keep insurance premiums affordable for poor households with limited incomes.

Integrating insurance into existing credit distribution systems has successfully reduced transactions costs for basic credit insurance. However, the layering of insurance onto a credit product means the client only has coverage when he or she has a loan. Many poor people would like to have insurance cover without being in debt.

Experience with insurance: Poor households are slow to understand the concept of insurance and are reluctant to commit to making regular premium payments for a future benefit, which is intangible to them. Poor people do not have the surplus cash to pay for a risk-management service, especially one they hope they will not need. It is difficult for them to justify paying premiums until after a risky event has occurred. Unfortunately, at that point, it is too late.

The level of trust required for an insurer to sell its products is greater than with other financial services. In the case of credit, the institution has to trust that the borrower will be willing and able to repay the loan. With savings, the roles are reversed: Clients have to trust that the institution will safeguard their deposits, but they can test this relationship by periodically withdrawing money. With insurance, the level of trust required of policyholders exceeds that required of depositors and savers, because the client will not know whether the insurer will keep its promise until some uncertain time in the future when the policyholder or his/her dependents make a claim. In addition, prospective clients in some areas have been subject to aggressive sales tactics by commercial insurers and now harbour a dislike or mistrust of all insurance providers.

Irregular household income flows: Traditional insurance products generally require a fixed amount to be paid on a regular basis. However, low-income households have difficulties maintaining a regular contribution schedule, given substantial fluctuations in their sources of income. If insurance is to be bought by these households, flexible premium payment options that do not jeopardise their household budget must be designed.

Affordability of premiums: Microinsurers face the challenge of offering insurance coverage at a price within the financial ability of the poor households while ensuring their own financial sustainability. One response to this challenge is to limit the coverage provided. This may not fulfil the needs of the low-income households.

A number of pilot projects are being run to establish what types of insurance can be offered profitably and to which policyholders. Early indications suggest that well-designed life insurance products can sustainably serve a broad spectrum of clients, but there is insufficient evidence to draw even tentative conclusions regarding the depth of outreach for health and property insurance.

Differential pricing for different risks: Most of the microinsurance providers ask for a flat-rate premium for their policies. Although this increases the simplicity of the products and lowers the premium, it prevents the insurer from setting premiums in line with the actual risk levels of individual policyholders. As a result, low-risk policyholders pay more than they should, effectively subsidising the high- risk policyholders.

Limited understanding of insurance needs: Low-income households are highly exposed to many risks. Little effort has been made, however, to understand how this exposure translates into a need for insurance. Understanding this translation is further complicated by households’ unfamiliarity with the concept of insurance. Without this understanding, microinsurers run the risk of offering poorly designed and unsuitable products.

Limited financing: Where financially strong partners are not available, microinsurers face the challenge of financing the total cost of product development during the start-up phase. Also, until sufficient scale has been achieved, client acquisition costs and initial claims expenses can easily exceed revenues from premium payments for new insurers. Funding this start-up phase requires access to financing or reinsurance to act as a capital reserve. Lack of access to these sources can either prevent an insurer from beginning operations altogether or constrain its growth.

Lack of actuarial expertise: One of the most significant obstacles facing NGOs/MFIs/CBOs that intend to act as full-service insurers is a lack of actuarial expertise to set premiums and determine benefits accurately. Without this knowledge, potential microinsurers run the risk of either setting premiums too low or too high.

Limited products: Today’s poor households require a range of insurance products to mitigate the risks they face. Unfortunately, the majority of them are offered only life insurance products like credit life insurance. Very few insurers offer the health or property insurance that the poor people need most.

Climate change: Weather-related insurance has always posed a challenge to the insurance sector. These difficulties may be exacerbated by the increasing risk and unpredictability of extreme weather associated with climate change. Climate change will probably increase the demand for insurance, while at the same time increasing its cost. The challenge will be to find ways to make insurance more affordable by reducing administrative costs.

The next step forward

Microinsurance is still a new and evolving area for experimentation and research. Experience to date provides some useful lessons and is helpful in highlighting where further innovation, change, and experimentation is needed. Each challenge represents an opportunity for further research or experimentation to develop innovative solutions. Additional research is also needed to understand and assess the developmental impact of various types of microinsurance product.

Although it is too early to predict the impact microinsurance will have on low-income households and the institutions that work with them, various pilot projects and experiments have garnered a lot of interest amongst the stakeholders in furthering the development of microinsurance. Stakeholders like governments and donors need to focus more on the enabling environment, and commercial insurers need to focus on developing low-cost and need-based products and innovative distribution channels.